- Page 1

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

- Page 11

- Page 12

- Page 13

- Page 14

- Page 15

- Page 16

- Page 17

- Page 18

- Page 19

- Page 20

- Page 21

- Page 22

- Page 23

- Page 24

- Page 25

- Page 26

- Page 27

- Page 28

- Page 29

- Page 30

- Page 31

- Page 32

- Page 33

- Page 34

- Page 35

- Page 36

- Page 37

- Page 38

- Page 39

- Page 40

- Page 41

- Page 42

- Page 43

- Page 44

- Page 45

- Page 46

- Page 47

- Page 48

- Page 49

- Page 50

- Page 51

- Page 52

- Flash version

© UniFlip.com

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

- Page 11

- Page 12

- Page 13

- Page 14

- Page 15

- Page 16

- Page 17

- Page 18

- Page 19

- Page 20

- Page 21

- Page 22

- Page 23

- Page 24

- Page 25

- Page 26

- Page 27

- Page 28

- Page 29

- Page 30

- Page 31

- Page 32

- Page 33

- Page 34

- Page 35

- Page 36

- Page 37

- Page 38

- Page 39

- Page 40

- Page 41

- Page 42

- Page 43

- Page 44

- Page 45

- Page 46

- Page 47

- Page 48

- Page 49

- Page 50

- Page 51

- Page 52

- Flash version

© UniFlip.com

A

ngela Pandit was just finishing her freshman year in high school when she became sick with a bad cold. This wasn’t a typical infection. All her joints started to swell and flare up. Her wrist was swollen, and she experienced jaw pain. Her symptoms were so bad, she had to stop participating in swim team events. Angela was confused and did what any teenager would do: she went on the Internet! Her parents, Arvind and Yuhuan, were a bit more practical. They sought the advice of local physicians. Still, there were no answers. Over time, as symptoms persisted, it became apparent something was going on in Angela’s body that wasn’t being identified. Finally, after consultation with a pediatric rheumatologist, Angela was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Angela’s father recalls how he felt when he heard the news: “This whole diagnosis was nerve-racking for me and my wife. I was in a state of denial. I said, ‘This can’t happen to Angela.’ Even doctors initially were not thinking juvenile arthritis.” There was no history of arthritis in the family, which made the diagnosis even more mystifying. Angela went back to the web to search. “When I found out I had this disease, I had the worst in my mind. When you Google, you see the worst scenario,” she says. “But it didn’t strike me as something too terrible. It’s a disease that’s usually associated with older people.”

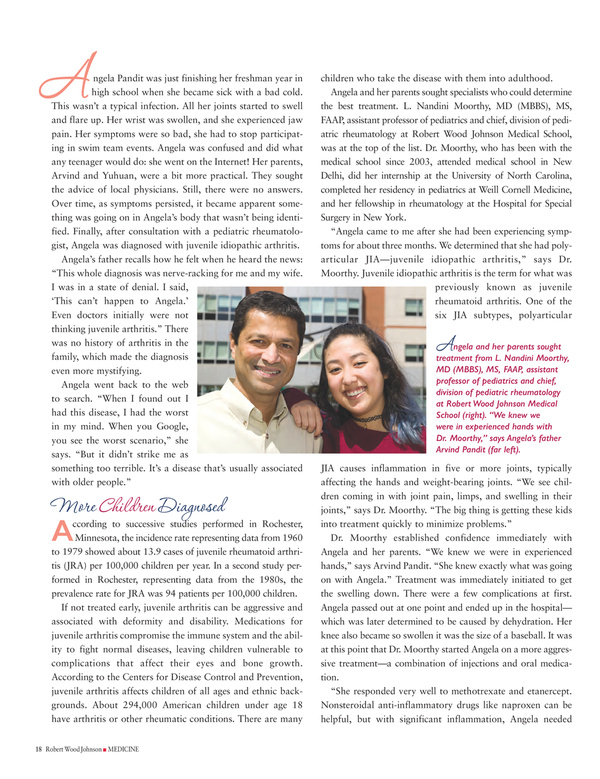

children who take the disease with them into adulthood. Angela and her parents sought specialists who could determine the best treatment. L. Nandini Moorthy, MD (MBBS), MS, FAAP, assistant professor of pediatrics and chief, division of pediatric rheumatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, was at the top of the list. Dr. Moorthy, who has been with the medical school since 2003, attended medical school in New Delhi, did her internship at the University of North Carolina, completed her residency in pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine, and her fellowship in rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. “Angela came to me after she had been experiencing symptoms for about three months. We determined that she had polyarticular JIA—juvenile idiopathic arthritis,” says Dr. Moorthy. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the term for what was previously known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. One of the six JIA subtypes, polyarticular

ngela and her parents sought treatment from L. Nandini Moorthy, MD (MBBS), MS, FAAP, assistant professor of pediatrics and chief, division of pediatric rheumatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (right). “We knew we were in experienced hands with Dr. Moorthy,” says Angela’s father Arvind Pandit (far left).

A

ccording to successive studies performed in Rochester, Minnesota, the incidence rate representing data from 1960 to 1979 showed about 13.9 cases of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) per 100,000 children per year. In a second study performed in Rochester, representing data from the 1980s, the prevalence rate for JRA was 94 patients per 100,000 children. If not treated early, juvenile arthritis can be aggressive and associated with deformity and disability. Medications for juvenile arthritis compromise the immune system and the ability to fight normal diseases, leaving children vulnerable to complications that affect their eyes and bone growth. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, juvenile arthritis affects children of all ages and ethnic backgrounds. About 294,000 American children under age 18 have arthritis or other rheumatic conditions. There are many

18 Robert Wood Johnson I MEDICINE

A

More Children Diagnosed

JIA causes inflammation in five or more joints, typically affecting the hands and weight-bearing joints. “We see children coming in with joint pain, limps, and swelling in their joints,” says Dr. Moorthy. “The big thing is getting these kids into treatment quickly to minimize problems.” Dr. Moorthy established confidence immediately with Angela and her parents. “We knew we were in experienced hands,” says Arvind Pandit. “She knew exactly what was going on with Angela.” Treatment was immediately initiated to get the swelling down. There were a few complications at first. Angela passed out at one point and ended up in the hospital— which was later determined to be caused by dehydration. Her knee also became so swollen it was the size of a baseball. It was at this point that Dr. Moorthy started Angela on a more aggressive treatment—a combination of injections and oral medication. “She responded very well to methotrexate and etanercept. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like naproxen can be helpful, but with significant inflammation, Angela needed