A Publication for Alumni & Friends of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Enhancing Professionalism, Creating Awareness of Health Inequities, Integrating Science and Practice

New Curriculum Meets Challenges that Await Tomorrow’s Physicians

Always forward thinking, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School faculty planned for a new medical education curriculum during 2020, working in a virtual environment strained due to the unique challenges of the pandemic. The Office of Education, along with the medical school’s Curriculum Committee and a cohort of medical students, worked in partnership toward reforming and revitalizing the educational plan to prepare our future physicians to meet the demands of an ever-changing industry.

“We made a commitment to pursue curriculum revisions despite the challenges during the past year; COVID-19 was not a reason to stop the process,” says Carol A. Terregino, MD, ’86, senior associate dean for education and academic affairs. “Essential to that process were our faculty, both clinical and basic science, who simultaneously adapted their courses to provide online learning during the pandemic, while reforming the curriculum for our future medical students.”

The importance of the faculty’s role can’t be emphasized enough, according to Dr. Terregino, as faculty model critical thinking skills and patient-centered care, in addition to teaching foundational knowledge of medicine.

Meigra Chin, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine, serves as chair of the curriculum committee and helped lead the educational transition. “Development of curricula is a collaborative effort between the faculty who educate our students and the faculty administrators, who ensure its administration with continuity across the preclinical and clinical years,” she says.

Diana Glendinning, PhD, associate professor of neuroscience and cell biology, and vice chair of the curriculum committee, concurs.

“With the leadership of Dean Terregino, we created a model for the new curriculum, including philosophies for best teaching, block and intersession designs, assessment and clinical and foundational sciences collaboration, and integration,” she says. “The process of meeting and planning together virtually has been rewarding. We have built strong teams and new collaborations.”

“A core group of enthusiastic educators at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School devoted significant time to re-evaluate and prioritize educational concepts, maximize efficiency, and develop our own high-quality educational resources. The enthusiasm and intellectual curiosity that new curriculum discussions sparked among the educators and students were frankly inspiring and refreshing to see,” explains Igor Rybinnik, MD, associate professor of neurology, who directed the curriculum reform for the clinical years and clerkships, along with Sarang Kim, MD, associate professor of medicine.

The collaborative effort also engaged medical students, 17 of whom were chosen as curriculum reform fellows, who worked together in small virtual groups to ensure the student voice was included.

“Analogous to patients as stakeholders in their care, our medical students are the prime stakeholders for their medical education,” says Dr. Terregino. “The engagement of medical students as curriculum reform fellows has allowed them to co-construct, along with faculty, major curricular elements.”

According to Dr. Terregino, the fellows worked with faculty across eight areas: professional development and professionalism; integration of foundational and clinical science across the preclerkship and clerkship phases; health equity, and inclusion and diversity; evidence-based medicine; experiential learning; integrated anatomy, procedures, and simulation; team dynamics; and learning, assessment, and evaluation.

“For faculty to be most effective in optimizing learning, they need to understand the learners—their learning styles and preferences. So, a student voice in the planning process was invaluable,” says Dr. Rybinnik.

The last curriculum reform at the medical school was in 2010, led by Siobhan A. Corbett, MD ’87, associate professor of surgery, a major contributor to the preclerkship curriculum. That adaptation was the first to integrate courses, weaving patient-centered care into the curriculum, and creating content and specialty boot camps to prepare graduating students for residency, resulting in Step exam scores that have exceeded national means.

In order to form the priorities of this transformation, the students, faculty, and staff were surveyed in 2020 as to what they wanted from a new curriculum. According to Dr. Chin, many of the responses focused on enhancing critical reasoning and knowledge for practice, rather than information recall. Respondents also wanted the curriculum to reflect modern technological advances and embrace innovative educational tools. Most importantly, they wanted the curriculum to address the perceived disconnect between the preclerkship and clerkship years and strengthen lifelong learning skills.

“The survey responses informed what we looked to accomplish,” says Dr. Chin. “The curriculum moves from a traditional approach—where students learn how things work, then how they don’t work correctly, followed by clinical training with patients—to an integrated approach where students learn normal and abnormal systems together throughout each year of medical school.”

Robert Lebeau, EdD, assistant professor and director, Office for Advancing Learning, Teaching, and Assessment (ALTA), who supported faculty in developing integrated learning activities and new approaches to assessment, adds, “The curriculum creates a new structure in which to fulfill the promise of the last revision: more fully integrating foundational science with clinical learning and providing fuller and more diverse opportunities for clinical learning.”

The collaboration among faculty and students, along with the survey responses, resulted in the creation of the “five C’s” to not only proliferate knowledge, but also strengthen skills critical to medical practice. Curiosity, critical thinking, clinical skills, competency, and compassion—these skills will be reinforced through continuity in practice over the duration of medical school.

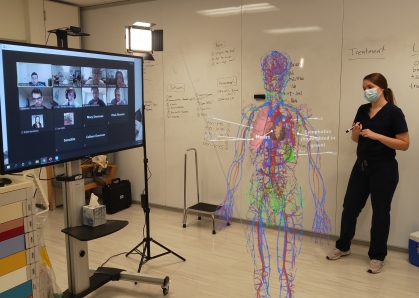

Toward supporting the five Cs, the structure of the new curriculum interlaces the foundational sciences with clinical training. It includes deliberate activities to encourage deep learning; earlier and more opportunities to participate in competitive subspecialty electives and sub-internships, and for scholarly projects; more time to refine critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills; and enhanced focus on learning patient-centered, compassionate care. According to Dr. Glendinning, the faculty members also envision incorporating more diverse teaching approaches, such as self-directed and case-based learning methods, as well as active classrooms.

The curriculum also will introduce students earlier into the clinical clerkships, lengthening the time for clinical education and patient interaction. The transition to earlier clerkships also allows for effective preparation of the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills exam. With the change of the Step 1 exam to pass/fail grading, the Step 2 exam scores are expected to be weighted more heavily by residency programs.

“In the new curriculum, the students will benefit from an enhanced educational experience in which both foundational and clinical concepts are clearly delineated, integrated together, and continually reinforced,” says Daniel S. Pilch, PhD, professor of pharmacology. “Such an educational experience will be invaluable to students in their preparations for board exams and will undoubtedly be reflected in their exam performance.”

Building physicianship skills is integral to the new curriculum. Although always included within the curriculum, physicianship will now be a specific focus of a sequential series of intersessions that the students will embark on from the very start of their education and then interwoven throughout the four years, allowing concepts to be revisited and reinforced. Its goal is to encourage professional and personal success.

“I am most excited for our plan during the first five weeks of medical school, which will set the groundwork for what it means to be a doctor; how to communicate with patients; introduce the basic skills of performing a physical exam; emphasize the importance of ethics, professionalism, and social determinants of health; and stimulate students to use critical thinking skills,” Dr. Terregino explains.

“In the preclerkship years, the intersessions are more about clinical experience and applied knowledge of foundational sciences in a clinical way, as well as physicianship,” adds Dr. Chin. “After students begin clerkships, the intersessions revisit the foundational sciences, allow for Step 2 preparation, electives, and research.”

“These intersessions allow for longitudinal, experiential learning,” explains Dr. Terregino. “They allow us as educators to be creative and create new experiences, but also allow students to achieve personal and professional development.”

Additionally, the planning committee incorporated structured time into the intersessions for wellness and personal development.

“It’s important to model self-care to our medical students so they learn early how to balance their careers with well-being,” says Dr. Terregino. “We are healers, and we have to heal ourselves.”

The curriculum framework is organized around threads, including evidenced-based medicine and health systems science, which were part of the 2010 revisions. The new curriculum incorporates a new thread, Health Equity, woven throughout foundational science courses and clinical clerkships.

“The idea was to develop a spiraling curriculum that operationalized a long-standing goal at our medical school to achieve enhanced exchange of information between the foundational courses and the clinical clerkships,” explains Dr. Pilch. “In addition, the new curriculum will expose students to the issue of implicit bias in health care, while also emphasizing pathways to addressing such bias.”

The inclusion of health equity and social determinants of health as a curricular thread was deemed essential by faculty and students alike. Although the medial school has always strived to reduce disparities and improve access for underserved communities through medical education, the reckoning for social justice and the greater impact of COVID-19 on people of color that occurred in 2020 emphasized the need to fortify learning about systemic racism in medicine for future physicians.

Shilpa Pai, MD, associate professor of pediatrics and director of resident education in advocacy and community health, is leading the development of the health equity thread along with Brad Kamitaki, MD, assistant professor of neurology.

According to Dr. Kamitaki, the new thread explores social determinants of health and works to create awareness about inequalities and biases in health care treatment. Its goal is to address systemic disparities in medicine, including racism, homophobia, and transphobia, to name a few, and to integrate thoughtful ways that physicians consider how gender, race, economic factors, housing, and other life dynamics affect the health of individuals.

The team is working to create awareness with the students so they not only understand the evidenced-based information, such as risk-based calculations of disease, but also comprehend why populations are more at-risk for certain diseases.

As an example, Dr. Pai and Dr. Kamataki explain that students traditionally learn which populations of people are more likely to be obese, a disease most often associated with Black, Latinx, and Native American populations. But, they say, it’s important to understand what underlies the development of disease. In terms of obesity, it’s not due to genetics but because, historically, people of color live in impoverished areas. Why do they live in these areas? Because of redlining, a government mandate that segregated communities and resulted in a lack of access to financial services, restricting mortgages to buy homes. Also, there are “food deserts” in underserved areas without easy access to grocery stores and healthy food choices at reasonable prices, they explain.

“We need to challenge our learners, and ourselves, to be very deliberate in our thinking,” says Dr. Kamataki. “We want our students to understand the impact of things we don’t see on our patients.”

Developing the curriculum around health equity includes an advisory committee of faculty across the medical school and working in partnership with community-based organizations that can more easily recognize the needs of the community and deliver resources beyond medicine, providing a bridge to improved community health.

They also are working with the medical students to create standards to ensure students consider social determinants of health and health disparities while caring for patients. The students also will visit the community organizations to better understand how to improve the lives of our patients more broadly.

For Dr. Pai, the past year was an example of three pandemics colliding—COVID-19, social justice, and poverty—underscoring the need to strengthen health equity education for students.

“It is a learning process for all of us; we are all evolving,” she says. “Being mindful of our unconscious biases, being more efficient with our time and deliberate in connecting patients with community organizations, we can provide better care for the whole patient.”

“Medical education is ultimately about improving patient’s lives,” says Dr. Glendinning. “Our hope is that the new curriculum will make a difference in patient’s lives by preparing our students to practice medicine with competence, sensitivity, and compassion.”

The new curriculum will be phased in during the next three years, with this year’s entering class—the Class of 2025—being the first to experience the new curriculum in its entirety.

“Given the relatively short time frame we developed the new curriculum from conception to implementation, the challenge was significant and required tremendous effort and commitment from both the basic sciences and clinical faculty, students, administrators, and staff involved in the process,” says Dr. Pilch. “It is only through the joint efforts of all these motivated and committed individuals that the curriculum came together. It has been my unique privilege to be a part of such an enthusiastic team united by a single common goal to advance the educational mission of our medical school.”

“Our mantra: we can always do better and we continuously think about quality improvement,” says Dr. Terregino. “This has been a great learning community for all of us as we move this forward. I am really proud of the amazing effort that was put forth.”